It is always difficult to predict what our digital future holds. The World Wide Web took us by storm. The emergence of e-books was long predicted, but still arrived suddenly. Social networking is still emerging and morphing. This entry is a long reflection on what has been with an eye to seeing if a look in the rearview mirror offers any clues as to a trajectory. The few conclusions at the end are no where near as much fun as the process of trying to see if we can detect anything about likely trajectories by looking at where we have been. We begin with a look at the broadest picture – computing and networking. We move on to look at the internet, and finally review the explosion of the World Wide Web. I conclude with a few observations that I believe are supported by the historical facts.

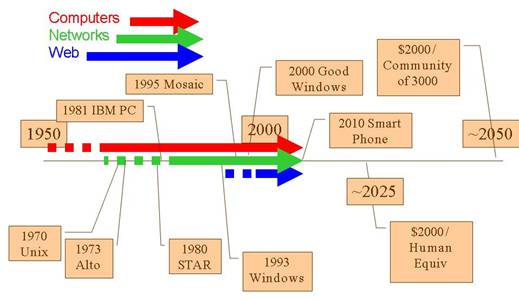

Looking at this broad, but selective timeline of computing and networking, I have tried to highlight a couple important events. While we are a full decade into the second half of the first century of computing, there is still some utility in reflecting on the difference between the first and second halves of the century. The reason for begging this indulgence has to do with “incunabula” and the book “Beyond Calculation” by Denning and Metcalfe, which was published in 1998 to celebrate the actual 50th anniversary of computing.

Incunabula is a term used by librarians to refer to books produced between 1453 and 1500 – the first half century of the disruptive technology of moveable type mass production printing. Incunabula books are remarkable in the degree to which they differ from each other and what we think of as books today. They were experiments. Indeed, the term incunabula is more broadly defined as any art or industry in the early stages of development. So we may think of what happened during the first half century of computing as computing in its early stages with lots of experimentation.

Denning and Metcalfe put together a wonderful compilation of articles in “Beyond Calculation.” The title provides a cornucopia of overlapping meanings. The most interesting is the observation made by several contributors that the era of computers that calculate is giving way to an era in which calculation is giving way to communication, collaboration, and coordination. We are in a period of significant experimentation and we are finding uses beyond calculation for this disruptive technology.

I observe three things using my fractured timeline. First, the Web is barely 20 years old, and for most people 10-15 might be more accurate and thus it is more bound by incunabula phenomenon than computing and networking. Second, while few things stand the test of time in this realm, the “desktop” is a notable exception. I am an unabashed fan of Xerox PARC, and always remind students that C. Peter McCullogh charged the first Director of PARC, George Pake with inventing “the information architecture of the office.” Out of that challenge came many things, but foremost was the “Alto” and the subsequent “Star” personal computers. And of all the innovations made manifest through these machines, a case can be made for the greatest being the WIMP (windows, icon, mouse, pointer) interface and the “desktop metaphor”. This is the same desktop, that you are sitting at today, more than 30 years later. We use programs hung on this metaphor to process information – to communicate and collaborate. Third, while predictions of exact trajectories vary, there is still solid support for Moore’s law – a continued doubling of computing power every 18 months or so. Every time I use my Droid X, marvel at the 1 Gigahertz device in my pocket that “doubles” as a phone and is always connected via four different networking technologies – wi-fi, 3G, Bluetooth, and GPS. In 2025, some suggest the personal device, which will likely rely on the grid, will have the storage capacity and processing capability of a single human. Around 2050, the optimists suggest it could have the capabilities of a community of 3000 humans. Even if we don’t reach quite this far, it is likely that my personal device will operate a series of agents operating around the clock on my behalf. Even if they are all idiot savants, I see them as at least capable of managing my calendar, knowing my travel preferences, keeping track of what I write, doing basic searches for me, etc. (I find it hard to imagine any way that I will be able to keep 3000 specialized assistants busy.)

So, the broad picture is one of immensely powerful personal assistants working to help me communicate, collaborate, coordinate, and calculate in such a way that they operate beyond the vision of Vannevar Bush as a intimate supplement to human memory, and dare I say, intellectual activity.

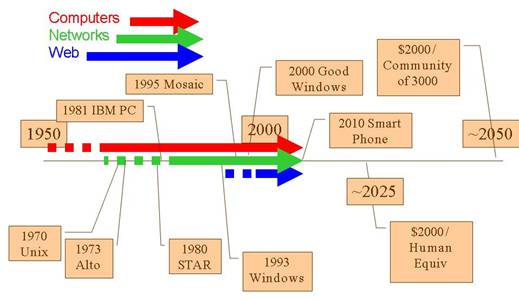

The growth and development of the internet is more difficult to track. The theory behind a packet switched network was laid out in the 1960s. The first nodes of what would become the internet were actually put in place as part of Arpanet beginning in 1969. The protocols that would become essential do the development of the packet switched network were developed through the 1970s – telnet in 1972, ftp in 1973, NCP in 1974, and SMTP(mail) in 1977. NCP was replaced by TCP/IP in 1982 and DNS was introduced in 1984. The World Wide Web (WWW) was released by CERN in 1991 and took off with the first graphic browser – Mosaic – in 1993.

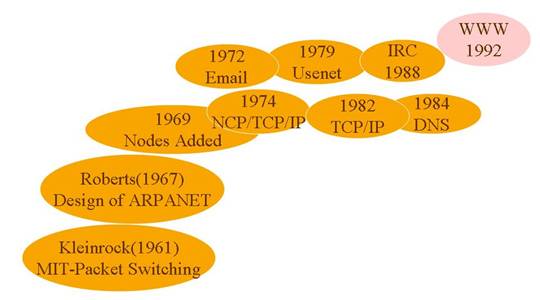

During the 1990s, things changed rapidly. We forget now about gopher and newsgroups, but they had their day. Early on file transfer dominated in terms of packets on the internet, with telnet connection packets being second, and mail third. It is a little hard to trace the growth of mail, but the phenomenal growth of the World Wide Web (WWW) is clearer. Web (http) traffic exceeded telnet packets in 1994 and ftp in 1995. Andrew Odlyzko’s 2003 paper on “Internet Traffic Growth” provides a balanced perspective on internet growth. He estimates that from 1990-1994 traffic about doubled every year from 1.0TB in 1990 to 16.3TB in 1994. Data for 1995 was not available, but by 1996 it had risen to 1500TB – the WWW explosion. He documents an ongoing growth rate of near 100% per year from 1996 through 2002 – from 1500TB to around 100,000TB. Obviously, both the WWW and P2P protocols were largely responsible for this growth. Further analysis shows SMTP traffic (estimated based on partial data) to have doubled about 4.5 times in 10 years. During roughly the same time, http traffic doubled 9 times! In 1994, mail traffic accounted for 16% of internet traffic and the web accounted for virtually none. By 2003, mail traffic had dropped to less than 2% and web traffic had increased to almost 50%.

The number of mail and web packets moved continues to increase at a rather amazing rate, i.e. there are more http packets this year than last. At the same time, given the totality of the bandwidth available, new applications are absorbing a larger percentage. The graphic below, published in wired magazine (http://www.wired.com/magazine/2010/08/ff_webrip/) is based on data from the Cooperative Association for Internet Data Analysis presents an interesting overview of the trends.

What does this suggest about the future? I think it suggests a couple things. It would seem reasonable to believe that we will continue to find new uses for the internet, which continues to grow at an astonishing rate. This network bandwidth has allowed us to begin to embrace a network centric model of computing. The desktop no longer needs to be a storage facility. Streaming gigabytes of data to watch a movie has become cheaper than mailing a DVD or driving to a store to pick it up. Music and video packets now crowd the internet based on both P2P and video outlets. Communication and entertainment applications absorb a growing percentage of the bandwidth with video alone accounting for more than half of all internet traffic in the US! While the number of packets devoted to the WWW continues to grow in absolute numbers, they have begun to decrease as a percentage of the total packets.

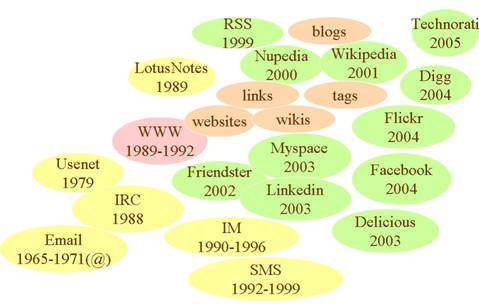

The graphic above attempts to show a couple different things. First, all of the technologies in yellow are non-web technologies. While most are internet technologies, I have included other seminal developments that have in one way or another influenced the development of the internet. The web gave birth to websites, links, tags, and wikis. These base capabilities were subsequently mashed up into Friendster, Wikipedia, and a variety of other collaborative efforts. The traditional web is being replaced by the social web. We spend relatively less “web time” searching for information (Google) and relatively more time sharing with friends (Facebook).

I am reluctant to say where the web is heading, but it would seem fair to suggest three simultaneous trends that will grow in a complimentary fashion. First, the web as a vast information store is not going to go away. It will continue to grow. While not as evident, the “semantic web” is slowly taking form – consider the special sections of structured information available in Wikipedia. Finally, it is very clear that a new “social web” is growing by leaps and bounds. This web provides rich new venues for communication and collaboration.

The psychologists have suggested various base motivations for humans. These include all the classic views from Freud to Adler to Maslow. There are several less well known views such as those of Viktor Frankl who makes a compelling case for a “will to meaning”. Johan Huizinga makes a compelling case in his book “Homo Ludens” for man the game player.

It is not hard to imagine story telling as a fundamental human motivation, and I suspect that there a scholarly work somewhere that draws a more complete picture. There is no doubt that humans are driven to communicate. This is what makes us different than all other species. This is what gives us an advantage. The disruptive technology of our time, computers and networks provide us with an opportunity to make unprecedented improvements in how we communicate. In 1959, Teilhard de Chardin’s The Future of Man was published. It consists of a compilation of pieces he wrote over the years including one on the development of global consciousness. On page162, Teilhard observes:

I am thinking of course, in the first place of the extraordinary network of radio and television communications which, perhaps anticipating the direct syntonization of brains through the mysterious power of telepathy, already link us all in a sort of “etherized” universal consciousness.

But I am also thinking of the insidious growth of those astonishing electronic computers which, pulsating signals at the rate of hundreds of thousands a second, not only relieve our brains of tedious and exhausting work, but, because they enhance the essential (and too little noted) factor of “speed of thought,” are also paving the way for a revolution in the sphere of research.

Teilhard’s philosophy/theology puts great stock in the ability of humans to be conscious of each other and the world. Communication and awareness are what most distinguish us as humans, and we strive to become more aware and more interconnected with each other. If there is a leitmotif in the story of the evolution of computing, networking, and the web, it is that we will support and encourage the development of the technology in ways that better enable us to communicate and increase our awareness of our world and other humans.